It is essentially a test meant to distinguish bots from humans, block the former and usher in the latter. That’s why it’s called the Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart. But because of its vast reach, and stellar text recognition capabilities, CAPTCHA software has been used in a range of other ways. Take a look.

HELPING RESEARCHERS READ ANCIENT TEXTS

For decades now, libraries, publishing houses and media companies attempting to digitise texts have run into a timeless problem: that of people gathering to squint at a word and go: What does that say?!

In some cases, manuscripts have frayed; in others, old newsprint has faded.

Using CAPTCHA, it turned out that scattered multitudes could help, by metaphorically gathering around and hazarding a guess at what the errant letters might be.

Here’s how it worked: Letters and words that character-recognition software could not reliably decipher were repurposed as CAPTCHA challenges, and presented in their distorted forms. As internet users around the world typed out the letter these called to mind for them, the results often produced an aha moment, confirming what archivists had guessed. At other times, the test generated user consensus strong enough to produce high-confidence transcriptions for major archives, including that of The New York Times.

That wasn’t all. The technology would change how archiving itself was done.

By 2007-08, NYT had reached out to Carnegie Mellon University, where CAPTCHA was developed, for help digitising its archive, which stretches back to 1851.

By May 2009, the results were clear. “So far, puzzling words in archives covering about 30 years have been deciphered with reCAPTCHAs,” Marc Frons, then chief technology officer for digital operations at NYT, said, in an article on the software in NYT.

Before this, typists had spent nearly 10 years transcribing material, and had covered just 27 years’ worth of archives. Using reCAPTCHA software, by 2011, the entire archive had been digitised and made searchable to the public.

THE FADING LOGO

Should users know if there is a larger mission at play in CAPTCHA tests?

The obvious answer is yes. But the aim of CAPTCHA is to keep friction to a minimum. It is already holding up traffic, simply by existing. So it was thought users needn’t know what else a test might be used for.

This, as with so much on the internet, would prove to be a slippery slope.

As early as 2007, certain websites began experimenting with engagement and ad-supported CAPTCHA, asking users to rate images or solve branded prompts, with unrevealed revenue models lurking in the background. Such attempts to monetise the verification process finally raised privacy concerns, and lost prominence.

FREE TRAINING MATERIAL FOR AI

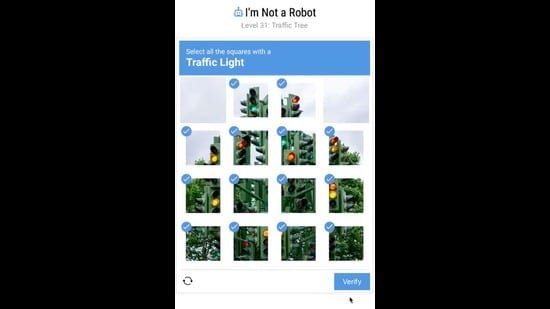

Image-led reCAPTCHA tests were famously used — and are still being used — to train algorithms ranging from AI models to software for self-driving cars.

Each time we click on a grid of images to identify parts of fire hydrants, bicycles or traffic signals, we are contributing to massive datasets. In this way, AI has learnt from all of us what a pigeon looks like; and self-driving programs have learnt how to view the world.

Users weren’t told this was what the clicks were being used for. Meanwhile, those who didn’t, or couldn’t, contribute found themselves locked out.

reCAPTCHA was particularly hard on the differently abled. This tendency of such tests in general to limit access to certain humans is now being addressed.

Government-run websites in India and around the world increasingly offer audio and text-based alternatives to imagery. Major public platforms in multilingual countries have begun to support verification in multiple languages.

Developers have also begun experimenting with designs-based tests in which the user must use an understanding of symmetry and spatial reasoning, rather than culture-specific references such as “crosswalk” or “traffic cone”.

KEEPING BOT-HELPERS AT BAY

An intriguing grey area in this world of bots vs humans involves CAPTCHA-solving services.

Such services hire very-low-paid workers to solve thousands of challenges a day, on behalf of automated systems. Since it is humans doing the solving, it doesn’t break existing laws. Since it is being done so a botnet can get in where it otherwise would not, it isn’t exactly kosher.

Such models spell trouble for websites that offer timebound services (concert tickets, transport companies) or contain highly sensitive data (banking and healthcare platforms). Such sites are forced to deploy increasingly complex CAPTCHA tests in attempts to deter and defeat such attempts.

The Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation (IRCTC), for instance, has been using increasingly intricate image- and math-based tests in its booking windows. Other sites have shrunk the time window within which an answer must be submitted.

A HACKER’S HANDY TOOL?

The test to prove you are a human is also now being used by hackers, ironically, to get in where they don’t belong. Fake CAPTCHA screens are designed to exploit the user’s instinct to simply solve the puzzle quickly. Once ushered into a system in this way, the program downloads malware onto the device and begins to pilfer data, hijack a browser or conduct other such activity.