Yahoo! — and to a lesser extent Hotmail — were the kings of the internet, in the late-1990s. Their free webmail services gave anyone with a modem a digital identity. But this openness had a fatal flaw: it was built on trust.

By 1999, that trust was being exploited by the first generation of spam bots.

The crisis revealed how vulnerable the internet had already become. A motivated teenager with a basic grasp of Python could write a simple script that could interact with websites directly. These programs didn’t need to understand the nuances of the internet. They just needed to recognise that, when they encountered an HTML field labelled “email_address”, they should inject a string of random characters, and when they saw a button labelled “Submit”, they should simulate a click.

These scripts transformed the internet into a playground for what became known as “script kiddies”: people who used pre-written code to cause chaos without truly understanding how it worked. The scripts were “headless”, meaning they didn’t need to load images or styling that a human would see. They operated on the raw text skeletons of websites, moving at the speed of the processor. Where a human might take two minutes to navigate a sign-up flow, a basic script could execute the same sequence in milliseconds.

By the time Yahoo! and Hotmail realised they had a problem, millions of fake accounts had been created by a handful of computers running on repeat.

This early automation was the primordial soup of the modern botnet.

Real-time attempts to monitor and track the origins of spam bots soon became far too unwieldy. Another solution would have to be found.

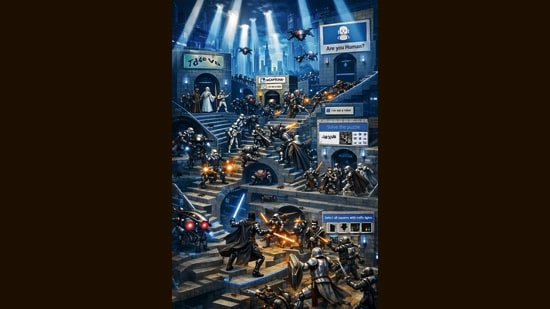

It was a team at Carnegie Mellon University, led by 21-year-old Luis von Ahn, that hit upon an answer in 2000: what came to be called the Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart, or CAPTCHA.

The concept was elegant in its irony. A machine would judge humanity. By displaying distorted text that humans could read through pattern recognition, but which baffled the optical character recognition software of the time, the team built a digital gate.

And for a few years, it worked. But as with any technological solution, the arms race had only just begun.

The next iteration, reCAPTCHA (also invented by von Ahn, in 2007), introduced the familiar grids of images, asking users to identify fire hydrants, bicycles or traffic signals. It was clever social engineering.

While users thought they were simply proving their status as humans in order to access a website, they were also providing free labour, the massive datasets required to train the next generation of artificial intelligence. AI learnt, from all of us, what a cycle looks like. Every crosswalk we identified helped teach self-driving cars how to view the world.

***

In 2018, a fundamental shift. Google, which acquired CAPTCHA from Carnegie Mellon in September 2009, launched reCAPTCHA v3. Instead of interrupting users with challenges, this version operates almost entirely in the background. Using a JavaScript API (or application programming interface), it assigns each interaction a score between 0.0 and 1.0, indicating how likely it is to be a bot (with 1.0 representing a high likelihood that the user is human).

This system became one of constant, invisible surveillance, judging users not by their ability to solve a puzzle but by the messiness of their mouse movements and the unpredictable rhythm of their scrolling.

This move introduced new problems. When the system couldn’t see the “messy” data it expected from standard users, it defaulted to suspicion. Power users who navigate with lightning-fast keyboard shortcuts, or those who use privacy-focused browsers that block tracking scripts, began triggering false positives for bot activity. Users found themselves trapped in infinite loops of “Please try again”, or blocked entirely from services without explanation.

The shift created particular challenges for accessibility. As with traditional CAPTCHA, reCAPTCHA v3 became a barrier for the differently abled, and for users of assistive devices. Platforms began to offer backup authentication options such as email codes and audio challenges, but these reintroduced the very friction the systems were attempting to eliminate.

***

Beneath these visible problems, a quiet shift had occurred in how identity itself is inferred online.

Modern bot detection increasingly relies on device fingerprinting: the aggregation of dozens or hundreds of small signals about a user’s environment. Screen resolution, installed fonts, GPU characteristics, audio stack behaviour, clock drift, network patterns, none of these are identifying on their own, but together they form a probabilistic silhouette of a device.

This fingerprint is difficult to convincingly forge.

It is also difficult to escape.

Users who take deliberate steps to protect their privacy, by disabling JavaScript, randomising user agents, blocking trackers, or routing traffic through virtual private networks or VPNs, often end up with fingerprints that are statistically rare. In systems trained to detect anomalies, rarity itself is suspicious.

This creates an inversion of the early internet’s values. Where anonymity was once a default, it is now treated as a sign of potential threat. The more opaque one chooses to be, the more friction one can expect to encounter. Trust is no longer granted by credentials alone, but by conformity to an expected pattern.

While it is still true that the gatekeeper doesn’t need to know who you are; it only needs to know you behave like others it has seen before… in order to meet that bar, well, you must tell it at least a little about who you are.

***

Meanwhile, the bots are getting faster, cheaper and smarter. Sophisticated programs can mimic human clicks and even solve basic image puzzles using AI.

With AI now a tool on both sides, the battle is shifting into higher gear.

Rather than trying to beat bots back, algorithms created by companies such as Arkose Labs are flipping the script — by simply giving them plenty to do.

In the world of high-stakes cybercrime, return on investment is the only metric that matters. If orchestrating an attack costs more in electricity and server time than the data is worth, the attacker will simply walk away.

So modern proof-of-work systems force the visitor’s computer to solve complex background mathematical puzzles. For a legitimate human user with a modern device, the task is a minor background blip. But for a botnet attempting millions of concurrent logins, this becomes prohibitively expensive.

In this strategy of deliberate inefficiency, the system lets the botnet churn away, burning through CPU cycles and electricity. By the time it submits its answers, it has already revealed its mechanical nature through its persistence. The gatekeeper won’t let it in.

That may be the battle won, but it won’t be the end of the war.

We’ve reached the point where AI can act so much like us that we have to invent increasingly complex ways to prove we aren’t them. As we use artificial intelligence to automate more of the internet’s basic interactions, we risk removing the accessible entry points that once allowed everyone to participate.

Meanwhile, the gatekeepers are invisible, the tests are behavioural, and the cost of entry is a constant stream of data about how we move and think. In our effort to keep the bots out, we’ve created a system that requires us to be watched, tracked and tasked invisibly, simply to prove we’re human.

The question now isn’t whether we can stay ahead of the bots. Like the Red Queen in Lewis Carroll’s Alice tale, it’s how fast we can run, just to stay in the same place.

Except it isn’t the same place, is it? We already no longer have the openness and anonymity that made the internet so revolutionary to begin with.

(K Narayanan writes on films, videogames, books and occasionally technology)