There isn’t a lot of whimsy on the police force. But look hard enough, and the tinsel sparkle of dreams will glimmer through.

One such man in khaki with technicolour dreams is Shivaraju BS, 46. This is his story.

It all started, he says, with his mother Gowramma (who goes by only one name), in the village of Bannikuppe in Karnataka’s Ramanagara district, about 50 km south of Bengaluru.

Gowramma wrapped his childhood in lore; there was little else to decorate it with.

On their meagre farm, with a largely absent father and money scarce, they would escape into reimagined worlds, enacting tales from the Mahabharata and Ramayana.

The isolation and poverty still left their mark. “Whenever I visited other people’s homes as a child,” he says, “I felt a pain when I saw family photographs on the walls.” He and his mother had memories to capture, he thought. Would they ever have the means to do it?

His maternal grandfather, a local folk-theatre actor named Dasappa, saw his love of the performing arts and introduced him to local actors and artists. This gave the boy a sense of a larger world out there, one that he might one day join.

In this way, the years passed. By 21, Shivaraju had secured a job as a police constable in Bengaluru. It was a first step in a very different journey.

One of the first things he bought was a sari for his mother, he says, and a digital camera (this being 2001) for himself. What a thrill it was, he says, “to finally be able to capture things I saw.”

As a policeman on the beat, he made it a point to befriend artists and photographers, particularly at a welcoming gallery called 1ShanthiRoad. These friends gave him a nickname he treasures: Cop Shiva.

In this way another 18 years passed, and Cop Shiva became eligible for voluntary retirement. He gave up the uniform and baton, and turned to the camera full-time. He takes commercial commissions to support himself and his mother. But when not on assignment, his lens takes on a life of its own.

Over the past seven years, Shivaraju has become a common sight across Bengaluru, chatting with and photographing ordinary people, migrants, people on the margins, as well as rural life in Bannikuppe. With each frame, he aims to capture for someone else the sense of self that he felt was so sorely missing from the walls of his own home.

That home, meanwhile, has been renovated and part of it converted into a studio of sorts.

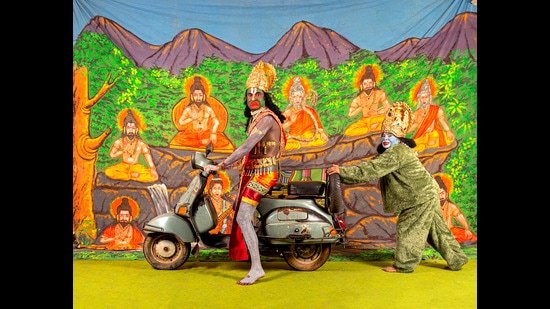

Floral backgrounds, bright rugs, sometimes even painted backdrops, are propped up against the wall, before which he and Gowramma then pose, making memories they can now capture.

The myths still underpin their tableaus.

“I loved photo studios as a child and always wished we had the money to go in and be photographed, so that is the look I have recreated,” he says. In this studio, he and Gowramma, friends and neighbours, use props and costume jewellery to dress as whatever character has taken their fancy that day.

“I never imagined my son would become the artist my father always wanted him to be,” Gowramma says. “I feel proud that he tells stories through pictures, and follows his heart.”

It didn’t end there. Last June, 133 portraits captured by Shivaraju were showcased in a solo exhibition titled No Longer a Memory, at Bengaluru’s Gallery Sumukha.

“One of the most wonderful aspects of putting together Cop Shiva’s show was the sheer volume of work to sift through. This wealth of choice speaks to his ambition as an artist,” says Joshua Muyiwa, curator of the show. “It also resonates with the spirit of his photography. The volume is turned up. It is maximalist and unabashed. It embraces its context, borrows heavily. But he always remixes the frame to make it his own.”

Yet another collection of his images, these themed on his mother, went on display from November to January, as part of a group show titled A Space Between Selves, at Delhi’s Art Heritage Gallery.

“For the longest time, my mother only had two saris. Now she has over 300, and she loves the bindi. I focus only on those aspects when I shoot her, not revealing her entire face,” Shivaraju says.

“Cop Shiva’s work brings together multiple perspectives—viewing the other and the self in isolation, while also turning his lens toward society at large,” adds Tariq Allana, associate director at Art Heritage. “Combined with elements of performance in the form of masquerade, his works bring to life not only the seen, but also the vivaciously imagined. Through this approach, narratives around identity, relationships, and power structures emerge organically from the work, compelling the viewer to step into the arresting world of a dynamic artist.”