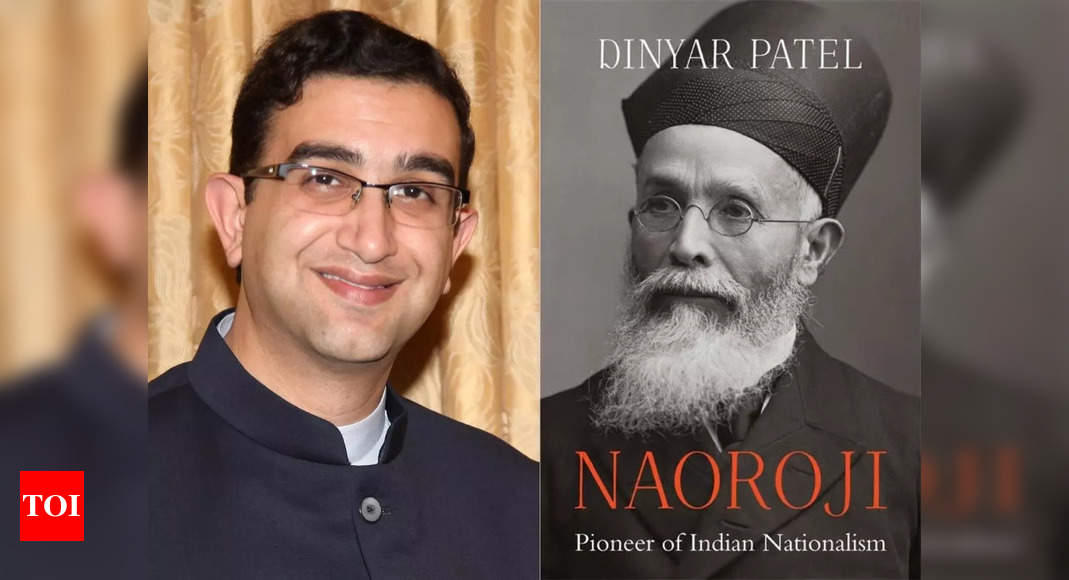

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: Author Dinyar Patel on his award-winning book, the thought behind writing it, next project, and more

In an exclusive interview with TOI Books, Patel discussed in detail his award-winning book, the thought behind writing it, next project, and more.

You wrote ‘Dadabhai Naoroji: Selected Private Papers’ in 2016, and now ‘Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism’. What about Naoroji fascinates you so much?

When I began writing on Naoroji, I didn’t anticipate writing this much. But his life and political career are so wide-ranging, and his activities were so multifarious, that I’ve found myself writing more and more over time. The key factor has been his personal papers – there is so much important material here, and to date far too few historians have extensively worked with them.

You have read and written about Naoroji extensively. What do you seek to attain by these books? Do you have any expectations from your readers?

Much of my scholarship has attempted to reverse common perceptions about early Indian nationalism. Above all, I hope that my book demonstrates that early nationalism was a vitally important phase in the creation of modern India: so many of the core ideas of Indian democracy and political culture were forged in this era, and the people who forged it, including Naoroji, have tended to receive short shrift in our historical accounts.

Naoroji was one of the founding members of the INC, was the first British MP of Indian origin, and even Gandhi called him “father of the nation”. However, what went wrong that we don’t hear or read much about such an important figure?

I think the simple answer is that so much happened in the short period between Naoroji’s death, in 1917, and Indian independence. In India, the political landscape transformed utterly beyond recognition between 1914 and 1920. The Indian experience of World War One, the Rowlatt Act, Jalianwala Bagh, the disappointments of the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, and, of course, the rise of Gandhi to political leadership destroyed any remaining faith in the type of constitutionalist politics which Naoroji adhered to throughout his life. By the end of his political career, Naoroji had a looming sense that this constitutionalist strategy was not working and freely admitted that he sometimes felt the temptation to rebel, but it took another generation to fully change course.

How relevant do you think Naoroji is in 2022? Where does he fit in the current socio-political-economic setting?

There is a lot that one can say when comparing the nationalism of Naoroji and his peers and the so-called nationalism we see bandied about today. But, when thinking about Naoroji’s relevance, another thing to keep in mind is the question of poverty. Naoroji understood that poverty was the biggest hurdle India faced: all of his politics flowed from a commitment to banish the wrenching impoverishment that stalked the country. I wish that today’s political leaders – regardless of party affiliation – shared this fervor and had the pluck to make real big-ticket reforms for economic development.

How and why does India need Naoroji?

I think that one important reason is that Naoroji, a Parsi, demonstrates how minorities have contributed so much to the modern fabric of India. Today, we seem to be in a race to the bottom in terms of the vilification of particular minorities. It is therefore quite remarkable to think that, 130 years ago, so many Indians acknowledged that a Parsi Zoroastrian from Bombay was their tallest political leader and loudly protested the idea that his religious affiliation could disqualify him from this status.

What were the most fascinating discoveries you made while researching your books on Naoroji?

For me, the most interesting experience was going through all of the miscellanea in his personal papers. Naoroji preserved pretty much all of his incoming correspondence, and he did not make any effort to weed out extraneous things like bills, receipts, junk mail, subscription notices, etc. Consequently, while going through his personal papers today, we get an unrivaled, fascinatingly detailed look at how an Indian lived and worked in Victorian Britain, navigating between two very different worlds and straddling so many different political and social spheres.

Anything you can tell us about your next book?

My next book will look more broadly at early Indian nationalism and delve into how nationalists envisioned a future India: how they thought about democracy, economic development, questions of governance, and so forth. I’m also exploring how this generation of Indian leaders engaged with the wider world and how they embraced all sorts of inputs and strategies.

Source link