China is Trying to Redefine Democracy, This Has Little to Do with America

The recent Chinese advocacy of a new model social democracy is not simply a response to the American-led Summit of Democracies. It has within it important policy moves aimed at stabilising the Chinese economy, adjusting the trajectory of its growth in relation to global developments and consolidating Communist Party of China’s (CPC) rule in the country. China’s rise as a geopolitical and economic power under an authoritarian one-party system has begun to offer a major challenge to the liberal democracy based on individual rights, multi-party elections, and rule of law. Immediately, it offers a response to the American effort to renew democracy in the face of internal and external challenges and to outcompete China on the economic front.

The Chinese clearly saw the Summit of Democracies which was attended by more than 100 countries, as a show of force by the United States (US). On December 4, five days before the meeting, China issued a White Paper called “China: Democracy that works” claiming that its “whole process people’s democracy” involves the people at all levels of decision-making. What is interesting, of course, is the power of the notion of “democracy” which China is not rejecting, but seeking to interpret it its own way.

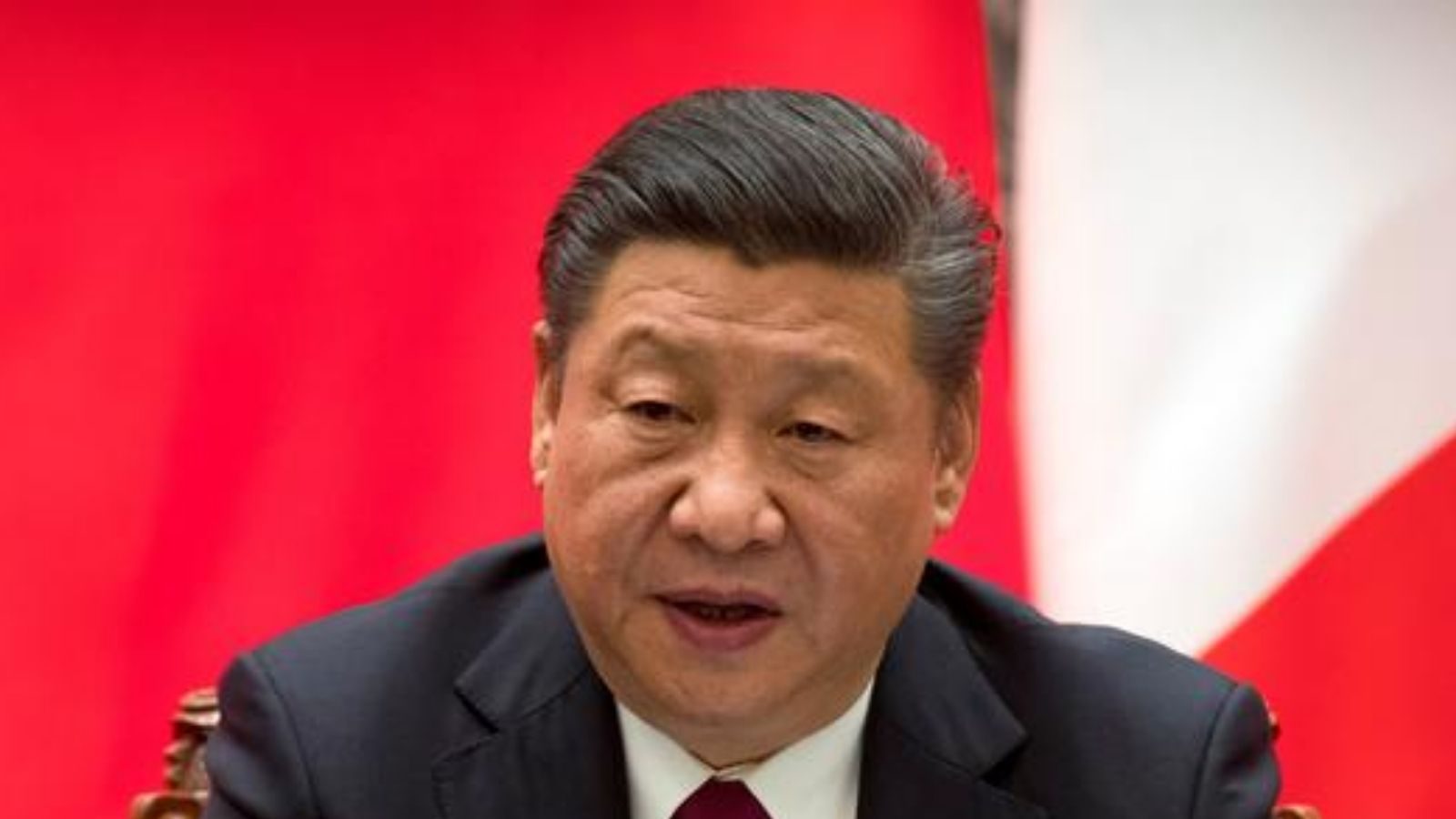

The change of the US-China relationship, from engagement to competition, has lent a sense of urgency to the Chinese efforts. Speaking at the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CPC on July 1 this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping said that China’s was a “whole process people’s democracy” which safeguarded social justice, resolved “imbalances and inadequacies of development”. It was “a new and uniquely Chinese path to modernisation”.

But the break with the US is not the key impetus for the CPC. Its roots lie in the Party’s own thinking about the need for economic and political efforts to ensure a continuance of the CPC’s rule. This was evident from the changed expression relating to “principal contradiction” facing China in the 19th Party Congress in 2017. This was the first change in 36 years. This hoary Marxist-Leninist-Maoist formulation provides an important guide to the developments since. In the Marxist parlance, these contradictions or dynamic opposing forces, drive change in a society. By identifying and resolving them, society moves forward, but if unsolved, the situation can lead to a breakdown and even revolution.

In his report to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, Xi declared that what China now faces “is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever growing needs for a better life.” In essence, there were unmet desires for better life among the middle class, better houses, education for their children, cleaner environment and so on. There were not just material needs, but those for “democracy, rule of law, fairness and justice, security and a better environment.”

Regulatory Crackdown

This alone has not been the push behind last couple of years of reforms in the banking sector, restructuring of local government debt, anti-monopoly measures against private sector giants, dealing with the real estate bubble, promoting data security and privacy protection. A lot of this would have been part of the continuing reform of the system, but it has definitely been accelerated by the trend towards decoupling China from the world economy. Most people think that it was the US, which since 2018 has pushed for the technological decoupling of China. Lesser known are China’s own effort to promote indigenous technology and keep out imports.

This was manifested in the 2000s in the way in which Beijing blocked off China from the internet and created its own internet universe behind the so-called “Great Firewall of China”. In mid-2020, China unveiled a “dual circulation” economic strategy to systematically reduce its dependence on overseas markets and technology. The emphasis would be on “internal circulation” of production, distribution, and consumption for development. The “external circulation” involving exports would be secondary. In this system, primacy would be given to local demand and consumption—the inner circulation—while the outer circulation and export would feed off domestic demand.

In 2021, we have seen a raft of measures aimed at fulfilling these goals. On one hand, the aim has been to boost technology innovation and push Chinese firms higher up in the global value chains and boost household incomes to stimulate domestic demand. On the other, it has made the effort to reduce inequalities to promote social stability. At the Central Economic Work conference in August 2021, Xi and his colleagues put forward the theme of “common prosperity” and the need to tackle major financial risks, to this end, they resolved to double down on the issues of debt and inequality. This involved a major crackdown on the hugely successful high-tech sector in China which the CPC felt had gotten out of hand.

The crackdown began with Jack Ma’s Alibaba which was fined US $2.8 billion in April 2021 for breaking anti-monopoly law by restricting competition on its online retail platform. Earlier in November 2020, its affiliate, the Ant Group, had to cancel a massive planned IPO which was stopped by financial regulators in Shanghai and Hong Kong days before it was to list.

In May, it was the turn of the food delivery giant Meituan which was fined US $533 million for engaging in anti-competitive practices such as forcing merchants to sell exclusively on its platform. This came with a series of measures to ameliorate the conditions under which the gig economy worked. In July, Chinese regulators tightened rules on Chinese companies listing in foreign stock exchanges. They said that this was occasioned by concerns over “data security, cross border data flow, and other confidential information management.” They said that they had been motivated to do this because of violations of rules, frauds, insider trading, and market manipulation. Caught in the middle of the rule change was the ride-hailing giant Didi, which had just made its New York stock debut. By the end of the year, the company announced that it would delist from the New York Stock Exchange.

In August, China passed a data protection law targeting private companies, who misuse data they have collected. The new law requires app makers to provide options to users over how their information can be used, or not used. It requires the companies to obtain consent before processing sensitive types of data such as biometrics, medical, health, location, and financial data.

Another move to rein in tech companies was through Chinese government taking a 1-percent stake and a board seat in two other top companies ByteDance and Sina Weibo. The former owns TikTok, though the government stake only covers some of the company’s other market video and information platforms. Sina Weibo is one of the biggest social media platforms in China providing a Twitter-like service. This year, the authorities also began a toughening of regulations around the purchase of flats and houses to contain speculative acquisitions and illegal deals. This is part of a wider crackdown on the housing sector, but one which has to be handled carefully since it comprises of one-third of Chinese economic activity and is currently mired in a liquidity crisis that has brought some of the country’s biggest developers like Evergrande to its knees.

Mixed in all this have been other crackdowns—on for profit private tuition companies which have been banned, gutting a multi-billion-dollar enterprise. Another set of curbs have hit gambling operations in Macau. Authorities say that they plan to regulate the sector to ensure that it does not get involved in money laundering and other illegal activities. Restrictions have also been placed on school going children playing online video games.

Needless to say the regulatory crackdown has been popular in China. Whether it is private tuition, video gaming, high-cost of housing, or the working conditions of lower-middle class people, the decisions have made life easier for the ordinary people and are popular.

However, many wonder whether or not the CPC is killing the golden goose. Demands that private companies set up CPC committees, or that the state buy shares in them with their own directors and directives to promote common prosperity could undermine the culture which has given China its valuable technology companies like Alibaba, Tencent, ByteDance, and Meituan, which were all founded by individual entrepreneurs and financed by venture capital.

But the system is currently buoyed by the performance of the Chinese economy, which in the nine years Xi has been in power has grown from being half of America’s size to 70 per cent, and the gap continues to narrow. Consumption has been the key basis of the economic performance and it is this which the Chinese hope to power their dual circulation economy based on domestic production, innovation, and higher consumption through raising wage rates.

There is, of course, another way at looking at these developments. They are as the setting of a stage for the 20th Party Congress in 2022, where Xi Jinping will be seeking a third term as the General Secretary of the CPC. Measures to reduce inequality, uphold middle-class values, cracking down on the rich, seek to create a stable and supportive environment for the Congress. Many of the measures would have been pursued anyway, but the Party Congress and the American competition provide the somewhat frenetic context in which they are taking place.

This article was first published on ORF.

The author is Distinguished Fellow at ORF. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Source link