Today, it’s her knees. Shalwar rolled up until the wadded hem forms a vice grip just above her knees. I ought to tell her to take the shalwar off if she wants a proper examination, but I wonder if she expects me to ask, and so I don’t. Possibly, she will conclude that I am as useless a physician as Dr Lal at JRH Awshadh. Possibly, she’ll stop coming.

It is Nivvi’s seventeenth visit to my clinic in as many months. Less? I flip the pages of her medical file and note that her first visit was fourteen months ago. Each visit sets her back two and a half thousand rupees, and that’s just my consulting fee. There are tests, the odd prescription. Three weeks pass, and there she is again, with a new problem.

We thought it was hypochondria, nurse Babykutty and I. We pored over her reports the first few months, listening carefully as she explained in detail her medical history of the last twenty-two years. She had kept every prescription from every doctor she had visited across six neighbourhoods in the city where she had lived all of her adult life. On her sixth visit, Babykutty let out an audible ‘Phew!’ before Nivvi had quite left the consulting room, and I had to frown in disapproval. On her seventh visit, Baby suggested that Nivvi derives a grim satisfaction from these medical appointments, and I allowed myself a rueful smile. Baby was emboldened to address Nivvi as ‘Aunty’, and to tell her that she was strong as a horse, nothing wrong with her.

Nivvi’s mouth was drawn into a tight, mirthless smile as she said, ‘Mare. The female is a mare. But I am not one. Perhaps you’d allow the doctor to make the diagnosis?’

Had I been younger, I would have risked a joke about the frequency of her visits but there was something about Nivvi’s watery grey eyes that reminded me of an injured wildcat. Each time I would consider telling her that she was perfectly fine, then I’d lose my nerve. I would extend a hand and she would put out her left arm. I’d check her blood pressure, feel her abdomen for knots, prescribe multivitamins and calcium and as many non-invasive tests as I could think of.

By her tenth visit, Babykutty and I had begun to talk about Nivvi during our lunch break.

‘Nivedita, she must be.’

‘Or Navya.’

‘Nice. But Navya is a modern choice,’ Babykutty insisted.

‘Her age means, it must be Nivedita.’

I fixed her with a mock glare. ‘Her age?’

‘Then what? Your age?’

And Baby burst out laughing.

Babykutty is a Godsend. She worked at Jehangir for five years before the hours got to her. Or perhaps it was the size of the hospital. Thirteen hundred daily outpatients, and the relentless stink of death. Anyhow, I was retiring from public hospital work but wanted to keep up a limited private practice. When I advertised for an assistant-receptionist-nurse, Baby responded. The first thing she said to me was, she wouldn’t work more than six hours a day.

I said, ‘Well! Thank you for coming in.’

Babykutty stayed in her chair, staring at me out of sad and slightly surprised eyes. I shifted in my chair.

‘Nobody works six hours in healthcare. That’s not even a full shift if you were a home nurse. Eight hours is minimum.’

Baby tilted her head to one side. ‘Eight hours, okay. Sixteen thousand rupees.’

I pretended to get busy with my prescription pad as I mumbled, ‘Eight thousand, starting salary. We’ll see after six months.’

She must have been desperate. I wondered, had the hospital let her go? But I didn’t call around to check. Whatever her reasons, Babykutty joined my clinic at eight thousand a month, and she did a decent job juggling appointments, prepping patients, and bandaging minor wounds. After six months, the sad film in her eyes seemed to have been peeled back and was replaced by a rainbow of expressions that seemed to change every hour. I hiked her pay to ten thousand and there it has stayed for a year now. We work six days a week, Baby and I. I’m here precisely eight hours and Baby, eight hours and twenty minutes, for she arrives ten minutes before me and locks up ten minutes after I’m gone.

Why me, I wonder? This is a perfectly normal clinic, one of dozens dotting each suburb of this sprawling city. There’s a homeopath across the road, a physiotherapist on the floor above. There used to be a dentist too, in the building, but he moved to bigger rooms on the far side of the park. Patients come and go all day. One afternoon, Nivvi walked in without an appointment or a referral from another doctor and ever since, every few weeks, she returns. For what?

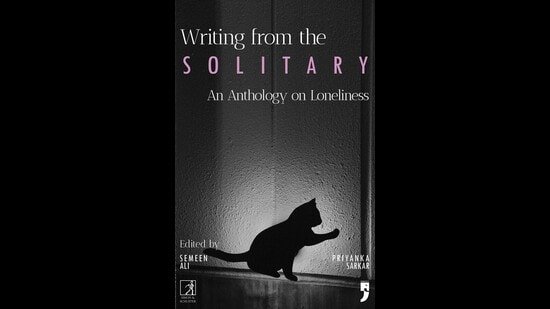

(Excerpted with permission from Writing from the Solitary: An Anthology on Loneliness, edited by Priyanka Sarkar and Semeen Ali, published by Yoda Press and Simon & Schuster; December 2025)